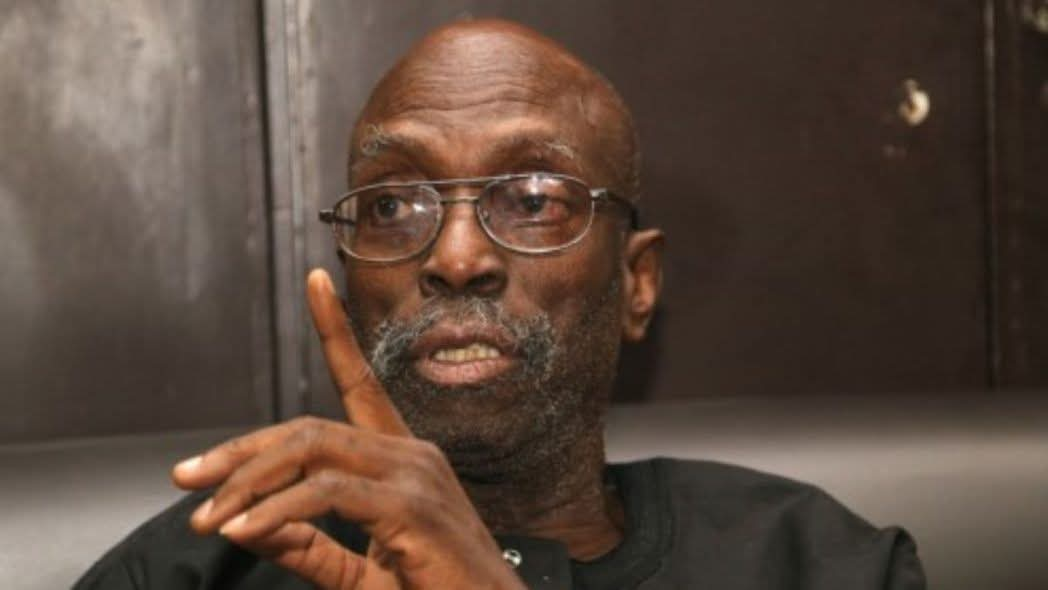

A tribute to Biodun Jeyifo, Marxist critic and scholar, exploring his intellectual legacy, activism, and influence in African literary thought.

By ‘Tosin Adeoti

I first heard the name Biodun Jeyifo on an ordinary afternoon.

I was in secondary school, standing in our sitting room with the nervous urgency of a teenager who had been handed a debate topic and had no idea how to construct an argument. My father listened without interruption. When I finished, he rose slowly and walked toward his bookshelf, scanning the spines with the ease of someone who knew exactly where each intellectual weapon was stored.

He pulled out “How Europe Underdeveloped Africa”. The pages were of course weathered, the margins dense with annotations written years earlier. As he flipped through it, he paused and said, “Check that shelf. Look for a book where Biodun Jeyifo is written.”

That was the first time I heard the name.

Years later, long after I had drifted toward capitalism and economic liberty, I encountered him again, as a formidable presence in African letters. Even when I disagreed with his ideological commitments, I could not ignore the scale of his influence.

On 11 February 2026, Professor Biodun Jeyifo died at the age of eighty, a few weeks after celebrating that milestone in Lagos. He had fought renal failure for years.

The story of Biodun Jeyifo’s life began with a shadow.

He was born on 5 January 1946 in Ibadan, at a time when the city stood at the centre of a decolonising Africa’s intellectual awakening. Ibadan in those years was restless with ideas. There were newspapers arguing with one another in print and political meetings stretching late into the night. In lecture halls and smoky cafés, students debated socialism and the future of a continent still shaking off imperial rule.

But even in infancy, his future seemed uncertain. At a public lecture marking his eightieth birthday in Lagos in January 2026, his lifelong friend Dr Yemi Ogunbiyi recalled a detail that cast that long-ago beginning in a stark light. Jeyifo had been born with a genetic condition that had already claimed the life of a sibling in infancy. Few expected him to survive childhood.

That knowledge stayed with him. Those who knew him often sensed in his work and conversation a certain urgency, an awareness that time was neither abundant nor guaranteed.

As a boy growing up in Ibadan in the 1950s and early 1960s, he absorbed the atmosphere around him. The city was not merely a place of learning. It was a place of argument. The University College Ibadan drew scholars from across the world. Writers, journalists, dramatists, and political thinkers moved through its streets. For an alert young mind, it was an education before education.

By the time he entered secondary school at Ibadan Boys High School, that atmosphere had already begun to shape him. He was not a quiet student. He watched, questioned, and increasingly, spoke.

At some point during his years there, dissatisfaction among the students reached a breaking point. Conditions in the school, both academic and administrative, had stirred resentment. Many complained in private. Few were willing to confront authority openly.

Jeyifo was.

Standing before school authorities, he publicly read a charter of demands on behalf of the students. For a teenager in that era, it was an extraordinary act.

The punishment followed swiftly. He was suspended.

For some, such an interruption would have been devastating. For him, it became a crucible. Unable to complete his studies in the conventional way, he prepared for his School Certificate examinations and A-levels as an external candidate. The outcome surprised even those who had regarded him as troublesome rather than brilliant. He excelled, and he did so decisively.

That performance opened the doors of the University of Ibadan, established in 1948, where he studied English. In 1970, he graduated with first-class honours, becoming only the third student in the school’s history to achieve that distinction. It was an early signal of the pattern his life would follow.

He moved on to New York University, earning a master’s degree in 1973 and a PhD in 1975 under the supervision of the great Richard Schechner. Those were years when theatre, performance studies, Marxism, and postcolonial thought were colliding in fertile ways. He absorbed it all.

But New York is not Nigeria where Jeyifo remained deeply tethered to. The country’s political volatility and its unrealised promises remained his central preoccupation.

When he returned to teach at the University of Ibadan and later at the Obafemi Awolowo University, he entered classrooms as more than a lecturer.

From Facebook posts I have read, students recall how he moved across the room, quoting passages from memory, pressing them to interrogate texts rather than admire them from a distance. Marxist literary criticism, cultural theory, political economy, these were not abstractions in his lectures. They were tools for reading the society outside the campus gates.

As the first president of the Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU), he stood at the centre of intellectual resistance during an era when military governments regarded critical thought with suspicion.

When the government accused lecturers, especially those in the Southwest, of not teaching what they were paid to teach — of indoctrinating their students with Marxism — Jeyifo retorted that they were indeed teaching what they were paid to teach, especially when the prescribed texts included works that dissected the moral and political failures of postcolonial governance. It was a response at once logical and audacious.

In 1987, after the university refused his request for unpaid leave to complete a commissioned scholarly work on Wole Soyinka, he resigned from Ife. He described the refusal as politically motivated, though he admitted that the decision had been incubating within him for some time.

He left Nigeria physically, but never intellectually.

After a year at Oberlin College, he joined Cornell University in 1989. Years later, in 2006, he moved to Harvard University.

Before his death, he held dual appointments at Cornell and Harvard. At Cornell, he served as Professor of English. At Harvard, he was Professor of African and African American Studies and of Comparative Literature. The duality suited him.

When he was moving to Harvard, the dean of his faculty reportedly asked him to write a note explaining why he remained a Marxist, despite the ideology being widely discredited. Why persist, the implication ran, in an ideology many considered obsolete?

His response was characteristically playful. In a tongue-in-cheek essay, he asked: “Who is afraid of JB’s Marxism?” He explained that his commitment was not doctrinaire but a framework for understanding capitalist modernity and its crises. According to him in that interview, that ended the conversation and he was left alone.

His book “Wole Soyinka: Politics, Poetics and Postcolonialism” remains a magisterial study. It won the American Library Association’s award for outstanding academic text and is widely regarded as the most comprehensive single-author study in African postcolonial criticism.

Where others saw obscurity in Soyinka’s work and complained of its density, Jeyifo saw modernist technique and discerned deliberate aesthetic strategy. His readings were meticulous without becoming sterile. They pulsed with admiration and a sense of shared intellectual struggle.

In January 2026, Lagos gathered to celebrate his eightieth birthday at the Wole Soyinka Centre for Investigative Journalism. The event carried the warmth of reunion. Former students travelled long distances. Speeches were delivered. Professor Wole Soyinka attended as guest of honour.

One of the speakers, his former student Priyamvada Gopal, now Professor of Postcolonial Studies at the University of Cambridge, approached him after several years without contact, his first words were a Yoruba proverb: The young shall grow.

He said it softly.

It was a greeting but also a philosophy. He believed in intellectual inheritance, in the passing of ideas from one generation to another, in the slow growth of thought across time.

Biodun Jeyifo lived through colonialism’s final years, independence, military rule, exile, global academic fame, and the complicated democracy that followed. He argued, wrote, taught, provoked, encouraged.

He believed the world could be changed. Even those who disagreed with his politics often found themselves compelled by the clarity of his brilliant mind.

On the morning after his death, many people reached for the phone to call someone they had not spoken to in years. That impulse, perhaps, is part of his legacy.

The young shall grow, he had said.

And somewhere, in the quiet determination of students discovering difficult ideas for the first time, they will.